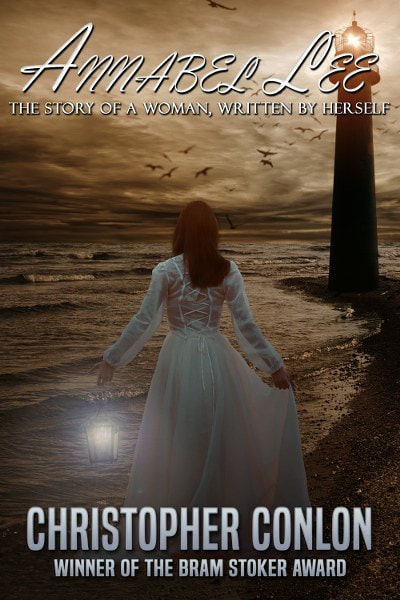

Annabel

Lee:

The

Story of a Woman, Written By Herself

by

Christopher Conlon

Genre:

Historical Gothic

Everybody

knows Edgar Allan Poe’s “Annabel Lee”—but who was she really?

In this haunting and evocative novel, Christopher Conlon (“one of

the preeminent names in contemporary literary horror”—Booklist)

imagines a life for one of literature’s most renowned characters.

Hers is a chronicle even more thrilling, doom-haunted, and tragic

than Poe himself could have conceived, for here Annabel Lee tells her

own story in her own words…for the first time.

Amazon

* Google

* Smashwords

In my memories of childhood it is always raining. I am sitting in the little nook off our kitchen, a snug recessed space just sizable enough for a plain armchair and small side table on which rests in its saucer a cup of steaming, aromatic tea. Three windows in a semicircular arrangement around me look out on the garden, the fields beyond it, and the blue hills in the distance: the very landscape, it may be said, of my early youth. In my lap rests the book I am currently reading, usually a novel from Father’s library—Walter Scott perhaps, or Fanny Burney, or else the natural philosophers Mother worries are somehow inappropriate for my delicate feminine mind. Father, it should be said, emphatically does not believe his daughter to be so limited, and among his hundreds of handsome leather-bound volumes I am encouraged to graze at will.

I have looked up from my reading to watch the rain slide down the windowpanes, listening as it taps the rooftop and spatters the glass. I sip at my tea, a familiar, not unpleasant melancholy settling over my soul. The quiet seems eternal. The world, gray and glistening, seems timeless.

Chair, teacup, book—my brain’s private image of a period in my life which then gave the impression of stretching forever, but which in reality was no more than nine or ten years. As with all memory, the image is somehow both perfectly true and oddly misleading. Reduced from reality, oversimplified, this still life of myself in the little alcove off the kitchen is less an actual remembrance than a kind of representational one, a moment perhaps never really lived as I think I recall it but rather a fusion of different moments crystalized into a figurative whole.

Mayhap this is the reason it is always raining in these visions I have of times long ago, the falling showers a metaphor for a certain mood I believe, rightly or wrongly, permeated my childhood. For in truth the state of Maryland, in the eastern portion of which I was born and spent the first twelve years of my life, receives, according to my Farmer’s Almanac, only some forty inches of rain per annum—hardly the Noah-like deluge my mind seems to suggest. I know, intellectually, that there were many days that were cloudless and sun-blooming, and when I try, I can just picture the fields around our house on the outskirts of Grimsleytown as they would have been in spring—the Indian grass and bee balm, the bright daffodils and black-eyed Susans. And yet I am unsure if such memories are any more true than the picture of myself in the armchair looking at the raindrops trickling down the glass. They seem to have no staying power in my mind, no lasting reality. Are such remembrances truer, then, or less true than the others? All these years later, is there any way to tell—to be sure?

The one common point between these, so to say, competing memories is the fact that in all of them I am quite alone. I picture myself strolling in the garden, the umbrella in my hands protecting me from the wet; no one is with me—and yet I know that I walked in the garden hundreds of times with Father in all sorts of weather. Now there I am in town, looking in shop windows, umbrella again keeping me dry, and again I am alone, even as I know that this could not have been so. The downtown area was a forty-minute carriage ride from our house, a venturing-out I certainly would never have undertaken by myself; Father or Mother would invariably have accompanied me. And yet there they are, my memories: rain-drenched, solemn, and solitary.

And, at times, terrifying—for if I let my reverie continue, reliving my early girlhood or some approximated simulacrum of it, I invariably find that as I sit there in the alcove with my teacup and book the rain becomes stronger, steadier. The sky darkens until it is nearly like night. Thunder explodes. Lightning slashes the sky. The downpour batters the glass so strongly that I begin to fear the panes may burst. But that is not all. What were pleasant rain-moistened fields only a moment ago now seem, in the strange dim light, like something else altogether. The shapes of the trees and flowers and wild grasses seem to move in the darkness—not simply swaying with the wind but moving entirely on their own, as if they have somehow uprooted themselves and are sliding grotesquely, impossibly toward my little alcove. My breath comes fast as the trees and flowers and grasses enlarge, inflate, grow gigantically until they are toweringly tall in the lashing rain. Unconsciously I have placed my tea things on the table. My book has fallen from my lap onto the floor. I stand as the nightmare world slithers toward me, yards away from the glass, now feet, now inches. I try to turn but cannot. I try to scream but my throat is tight. I can only watch as the fantastic wild world looms up before me and I hear a sound now, an unnatural, unearthly moaning somehow emanating from the outside, from the terrible invaders themselves. They press against the glass—there is a scraping sound like knives on bone—the glass bends inward—

Of course, the reader must think, this is but a little girl’s fancy. And indeed I agree. Obviously nothing like this ever occurred, or could have. Yet there is something to it, something that, as I have written, perhaps did not happen in a literal sense, but which nonetheless reflects something quite true, quite real, about my life—the sense of a melancholy peace suddenly turned to appalling, inexplicable horror. That is a process with which I am, alas, all too familiar.

Christopher

Conlon (b. 1962) is best known as the editor of the Bram Stoker

Award-winning anthology "He Is Legend" (Gauntlet/Tor), a

tribute to author Richard Matheson which was reprinted by the Science

Fiction Book Club and in multiple foreign translations. His novel

"Savaging the Dark" was included in Booklist's "Top

Ten: Horror" for 2015 (starred review) and acclaimed by Paste

Magazine both as one of the 21 Best Horror Books of the 21st Century

and as one of the 50 Best Horror Novels of All Time. Two of his

earlier novels, "Midnight on Mourn Street" and "A

Matrix of Angels," were finalists for the Stoker Award, and he

has written numerous collections of stories and poems along with two

full-length stage plays. A former Peace Corps Volunteer, Conlon holds

an M.A. in American Literature from the University of Maryland and

lives in the Washington, DC area.

Follow

the tour HERE

for exclusive excerpts, guest posts and a giveaway!

No comments:

Post a Comment