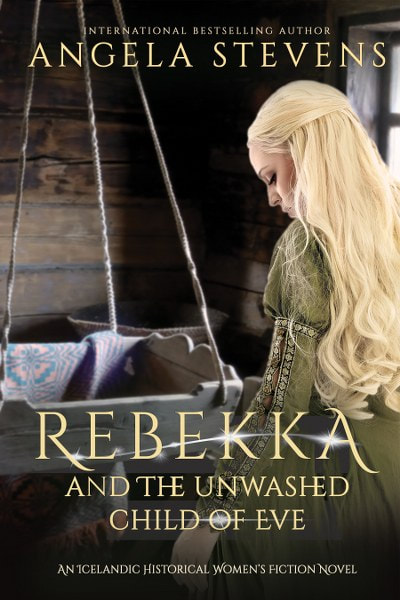

Rebekka and the Unwashed Child of Eve, Chapter 1: (2916 words)

Christmas Eve, 1871

Candlelight flickered across the creamy plaster walls of the tiny chapel, casting fluid, dancing shadows that dimmed and brightened as the parishioners wriggled on the hard, pristine white pews. The God-fearing Icelanders, who’d braved the weather to celebrate Christmas Eve, filled the benches until they overflowed, leaving the flustered latecomers to gather along the back wall, peeling off and piling their heavy warm winter clothing at their feet.

While Father Pétur droned through his sermon, Rebekka grew listless in the stuffy atmosphere, and as hard as she tried, she couldn’t lock into the Lord’s words. Her essence drifted out of her body, floating to the rafters where it hovered, gazing down on the holy and unholy alike.

Below her drifting spirit, Bryndís’s stepson, Viktor, sat straight-backed, his finger tugging and scratching at the collar of his too-small white shirt. His heavy eyelids closed and the boy’s head nodded forward, but a quick, sharp elbow from his stepmother jerked him awake. As good a man as Father Pétur was, his monotonous tone tested the eyelids of most of the congregation. For poor Viktor, he was losing the fight; he’d slaved away on his father’s croft for sixteen long hours, then trekked a mile across the frozen snow to the service. The boy was exhausted, and despite his strong will to be good, the need for sleep won out.

Although Pétur made his living speaking God’s words to the masses, his sermons blurred into one long stream of consciousness with neither excitement nor fear punctuating them. Why, even Jesus himself might fail to take inspiration or hope, let alone the heathens crammed inside these whitewashed walls, Rebekka mused, as she surveyed the scene from the dust-laden beams.

With the little amusement on offer from the pulpit, Rebekka’s essence searched for entertainment elsewhere. On the front pew, Farmer Jón Jónasson sat with his plump wife and pretty pink-faced little girls. Dressed in neat, bright skirts and crisp white bodices decorated with intricate embroidery, the children’s Upphlutur stood out from the drab black woolen clothing the crofters and tenants’ children wore. They perched on hard pews beside their mother, their ankles crossed while their eyes were glued to the priest. But their father, Jón Jónasson was more animated. His gaze drifted around his workers and when his eyes met with those that toiled for him, they did so with kindness, bringing a warm smile and a nod of recognition.

A flutter of hair slipping from the confines of a frayed ribbon caught Rebekka’s attention, bringing it back to her own form. Although she turned twenty-five at the beginning of summer, she sat with stooped shoulders, weighted with sorrow and work. Calloused hands took on bent crone-like features as they wrung at her skirts, and the once golden tresses of her youth were now lank and dull. With skin as pale as the plastered walls, her thin lips drew down at the corners. There were five years of suffering etched into her once pretty face, and the rose-pink high cheekbones of youth became sallow and hollow, with angles too sharp and too harsh for a woman her age.

Finnur reached across Rebekka’s lap, threading his fingers through hers, administering an imperceptible squeeze. Accepting his solidarity, Rebekka glanced sideways at him, and as husband and wife regarded each other, the heavy black aura surrounding the couple lightened at the edges.

Poor Finnur’s face was as tired and drawn as his wife’s. His eyes showed as much sorrow as hers, and as that despair grew between them, Finnur’s gaze drifted to the floor. Wearily, he scratched at his beard, and Rebekka detected a sag in those once strong, broad shoulders.

Before their pitifulness weighed too heavy, she sought out the stained-glass window as a way of comfort. It was a remarkable piece, imported from Europe, that had travelled much further as an inanimate object than her animated body could ever imagine. She examined every tiny blue square, counted each hand-cut piece, and focused in on the smallest detail of the design until she could no longer remember what it depicted.

“And now a story requested by Jón Jónasson’s beautiful girls, as a reminder on this Christmas Eve night, of those that remain hidden from us, yet reside in the rocks that scatter our land.” Father Pétur’s eyes rolled up to the church roof, and Rebekka wondered if he was apologizing to God for the heathen story he was about to tell.

“Let us take a moment to remember whence they came to be, and how their existence relates to us.” To everyone’s delight, and Father Pétur’s dismay, the farmer’s children had selected a heavy book that Rebekka at once recognized as volume 1 of Jón Árnason, Icelandic Legends. No matter how hard Father Pétur tried, he could not rid what he referred to as ‘superstitious nonsense’ from his church. Over the years, he had stopped trying, and had given up scolding his parishioners when they perpetuated the huldufólk myths.

“Once, when the world was in its infancy, God Almighty came to visit Adam and Eve. They received him with joy and showed him everything they had in the house. They brought their children to him, and these He found promising and full of hope.”

As Pétur cleared his throat, the parishioners awakened from their stupor, listening with interest. “Then He asked Eve whether she had no other children than those whom she now showed to Him, and she said, ‘None.’ But this was untrue. It so happened that Eve had not finished washing all of her children, and feeling ashamed to bring them to God so dirty, she hid the unwashed ones. But this, God knew well, and He said to her, ‘What man hides from God, God will hide from man.’”

For the first time that night, Pétur had the full attention of his flock, and they waited with bated breath for the story’s conclusion, despite each and every one knowing it by heart.

“These unwashed children immediately became invisible and took up home in mounds and hills and rocks. From these unwashed children of Eve, the álfar descended, but we men trace our lineage through those children of Eve whom were openly shown to God. And it is only by the will and desire of the álfar themselves that man can ever see them.”

Father Pétur closed the dense book, and as its crisp pages fluttered shut with a whisper, it created a sound so soft that it didn’t even muster an echo, yet its breathless voice called Rebekka’s essence back to her body.

Murmurs spread through the congregation as Pétur began his closing words. “Before you make your way back to your homes, I hope you will join me in prayer for two of our congregates who suffer today. Two days past, Rebekka Jónsdóttir and Finnur Einarsson’s daughter went unto God before drawing her first breath. My heart is filled with great sadness for you both. Please, let us pray.”

Rebekka sank into the pew wishing she could be as invisible as an álfar and disappear into the wooden bench or rock floor. She wanted to hide her form from the pitying eyes that looked her way. But she was not unwashed, and the men and women around her saw her, even though they shut their eyes in prayer. Rebekka feared what they saw was an unfortunate woman, a maid that had no children clinging to her skirts, a maid found so unworthy, that God denied her the joy of birthing a living, breathing child.

Even the barren stared with pity in their eyes. For in a cruel twist, God allowed her to conceive, to witness that heady joy in her heart, to hope, to dream, but her sins must be the foulest—though she could not remember what she might have done for Him to play with her heart so wickedly that He let her go through childbirth, only to take the breath from her babe before she heard it cry.

“Amen.” Father Pétur made his way to the rear of the chapel, and the congregation struggled to their feet.

Stretching and chattering, they scrambled to collect their possessions and wrap their weary bodies in wool and felt against the frigid air awaiting them on their journey home. The ritual of pulling on thick sweaters, heavy coats, warm woolen mittens, huge fur-lined hats, and long felted scarves played out, and Rebekka looked to her feet, her impatience growing as the chatter escalated. What was wrong with these people? Did they not want to get to their beds? It was close to midnight, and most needed to rise in a few hours to tackle their chores. Animals didn’t care that it was Christmas morning. Whatever the day, they demanded feeding and watering, and the dung in the stables still needed scraping from the straw and piling up for drying.

Rebekka hung back in the shadows of the gloomy chapel, waiting for the crowd to disperse, so she could leave without fuss.

Outside, the wind whipped up the new fallen snow, sending white tornados spinning across the landscape. Each time the heavy door opened, a flurry of mjöll skittered into the nave. It spiraled down the center aisle, toward the chancel, making the candle flames dance, and sending tall undulating shadows gyrating across the whitewashed walls. When the swirling snow ran out of energy, it hung in the air for a second, as if bewitched by the unseen fingers of the unwashed children. Just as Rebekka grew mesmerized at the particles unnatural dalliance, they fell, sprinkling her boots. A hush settled across the dwindling crowd as Mother Nature’s antics drew their eyes to Rebekka’s hiding place. Bryndís and her gossiping friends’ eyes widened as the skittering flakes traversed the aisle and, one by one, fell at Rebekka’s feet.

She stared at the circle of snow. Pure and white, a halo highlighting her stained, worn sheepskin boots and threadbare woolen skirt. Too late, she realized her shabby state was not befitting the occasion.

Finnur’s gaze fell on her, and she could only imagine the shame she brought on him. His hands rang his felted hat and mittens, but paying no heed to the approaching gossips, he placed his arm around her shoulders, and with a forced smile, he willed one from her. When she couldn’t conjure it even for him, his blue eyes, already tarnished with unhappiness, dulled even further.

Removing his arm, he took her hand instead and squeezed her fingers. “We should not have come. I’m sorry, my love, this was too soon.”

Rebekka took a deep breath and drew on Finnur’s strength. “What? And give our neighbors more gossip? What choice did we have?” Any other time, they could have taken time to dwell on their loss, but Christmas Eve was the one night a year when heads were counted, making it impossible to avoid the service.

Finnur squared his shoulders and turned to greet Father Pétur and their friends.

Bryndís didn’t even bother to lower her voice as she filled in details to the surrounding ears eager for gossip. “She carried the baby closer to term this time—a full seven months.”

Father Pétur reached Rebekka first and placed his hand on her shoulder, but it gave her little comfort, and she attacked the man with a sharp tongue. “Why does God continue to punish us year after year? Finnur and I are good Christians and hospitable people.” She searched the man’s face, hoping to find answers. “We offer everyone who knocks on our door food, drink, and a bed for the night. We work hard, pay our taxes, have never shirked our responsibilities on the croft. Our love for each other is pure, neither mine nor my husband’s eyes have strayed to another. Can’t the Lord allow one of my babies to live?”

Finnur stepped closer, his hand finding hers once more, bolstering her as Bryndís and the others surrounded them.

“We should not expect preferential treatment from God, the life of your child is…” The stout woman beside Bryndís sounded confident, but Rebekka knew the woman had yet to conceive herself. The woman’s confidence wavered as Rebekka glared at her. “Well, you know… you must take precautions.”

With courage fueled by sorrow, Rebekka threw all her pent-up anger at the woman. “I consulted every mid-wife, psychic, and seer within twenty miles for guidance on how to make sure I had a successful pregnancy!”

Rebekka had been diligent, she had asked the traveling vagrants, and listened to every gossipy women’s superstitious stories. She gathered any advice—however bizarre—and followed each rule to the letter, so child number five had the strongest chance of life.

“As soon as I knew I was expecting, Finnur collected the ptarmigan feathered quilts from our home.” She’d never have forgiven herself, if she lay on one and condoned her baby to never being born.

“She did.” Bryndís confirmed to the audience. “Finnur brought them the very next day.”

“I dismantled the clothes lines,” which crisscrossed both the inside and outside of Rebekka’s home, making it possible to dry their outdoor clothing, “in case I stepped under one and caused the umbilical cord to strangle my child.”

Bryndís patted her back. “There, there. Seven months was closer to term, so much more viable than the… others.” Her voice trailed away. “Next time, there is a good chance it will go full term.”

Tears spilled down Rebekka’s cheeks. Next time? Couldn’t they see it was the hope that broke her heart?

“But she was so perfect. No harelip, I was careful not to eat with a cleft spoon.” The women sighed in sympathy. “I counted ten tiny exquisite fingers on her little hands.” Because she’d refused her favorite meal of seal flippers to prevent the baby being born with them. “But, despite all the child’s perfections—my care, the attention to detail—my poor baby girl came into this world without taking a single breath.” Rebekka’s neighbors cooed around her, but none could tell her what she might have done wrong.

Behind them, Magnùs’s deep low voice addressed Finnur. “I saw you dig a grave.”

“Aye.” With a single word, Finnur dismissed his madness.

Rebekka narrowed her eyes at the big brute of a man. “Sure, you would have done the same, Magnús.”

When the sun had crawled as high as it could on that Icelandic winter’s day, Finnur had broken his back for her. While she cradled the infant—imagining what her daughter’s cry sounded like and fantasizing about the babe suckling at her breast while she looked into eyes full of life—her beloved husband pulled on his warmest boots and went out onto the hjarn.

The packed frozen snow encased the earth. Finnur might have had more success digging through lava rock, but despite the impossibility of the task, Finnur attacked his responsibility with vigor, leaving Rebekka wondering where he found the strength. Was it grief or anger that spurred him on so?

She placed the newborn in the frozen ground. The little mound huddled between the plain markers of her four sisters, and as the last few minutes of precious winter daylight slipped away, Rebekka and Finnur piled rocks above their daughter to ensure her spirit didn’t return to the world.

“I saw the fire. You burnt the placenta?” Magnús raised an eyebrow. “How will that benefit the forsaken child in any way? A star to light her lifeless body serves no purpose.”

“It brought comfort to Rebekka,” Finnur answered resolutely.

And so it had.

As the meager half-light slipped from the winter sky, leaving the world black and dangerous, they’d watched a spark from the fire rise into the air. It transcended to the heavens, the ember’s red glow whitening and brightening in its ascent. The ember arched, settling into position over the humble grave, where it shimmered brighter than any other star in the sky, illuminating the frozen ground at their feet.

“There was a star,” Rebekka whispered.

Everyone’s eyes, save that of the priest, avoided hers. Father Pétur took her hand and patted it. “Then I am sure God is with you. He sent a star to watch over your daughter, and one day, He will reward you with a child. God is merciful, and may move in mysterious ways, but He recognizes the love you have to give.”

Rebekka held her breath, hoping to dam the flood of tears that threatened to fall.

Finnur came to her rescue. “Thank you, Father. I should get Rebekka home, as this has been an exhausting time for her, and she is weak from the birth.”

“Take care.” Pétur stepped back and the crowd shuffled out of the unfortunate couple’s way. “Hurry home before this weather takes hold.”

The couple pulled their wool coats closed, and, with her mittened hand still wrapped in Finnur’s, her noble husband guided Rebekka past their well-meaning neighbors. As the door opened, a large gust rushed into the church. With it, flew new snow that showered the dirt floor and settled on the wooden pews. Rebekka shuddered at the ferocious wind that tangled her skirts and left her coat covered in white flakes.

Finnur pulled the felted hat over her ears and arranged her scarf closer to her throat. Then, with no care for who saw him, he placed a kiss on her cheek. “Let me take you home, my love.”

No comments:

Post a Comment